If you opened a sales org chart in the 1950s, you wouldn’t find a single AE, SDR, CSM, or CRO. Selling looked different then. Reps carried leather sample cases, memorized scripts, and drove long loops across their territory shaking hands with customers who bought hardware, telecom systems, and office machines in person.

But inside early companies like IBM and Xerox, something new was forming. They were inventing the structure every modern GTM team now relies on. Titles we take for granted today didn’t appear overnight. They stacked on top of one another across seventy years of business trends, technology shifts, and revenue experiments.

This is the origin story behind them.

When Corporate America Needed a Field Army (1950s–60s)

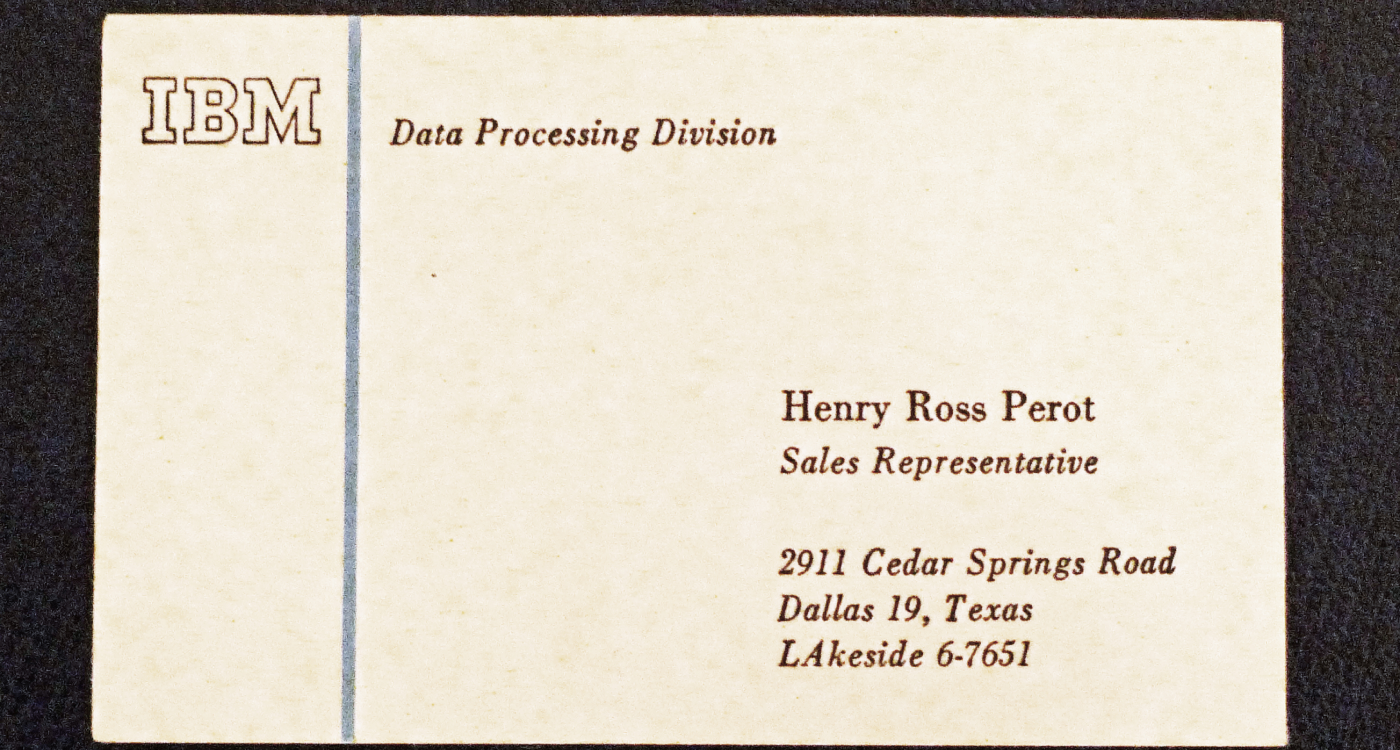

IBM was one of the earliest companies to treat selling as a formal discipline. A Territory Representative was the company’s foot soldier, responsible for a geographic region, not a vertical. Sales Engineers became common as products grew more technical.

Xerox took the same approach as it scaled the copier business. District Manager, Major Accounts Representative, and Systems Specialist showed up on business cards as the company expanded into hospitals, law firms, and universities.

By the end of the 1960s, the basic hierarchy of enterprise selling was already in place. There was the rep, the specialist, and the manager. Titles became a way to project professionalism in an era where the traveling salesperson stereotype still loomed large.

The AE Becomes a Star (1970s–80s)

The shift from electromechanical products to computing changed everything. Selling wasn’t about dropping off brochures anymore — it required technical fluency, problem-solving, and long sales cycles. That’s when the Account Executive stepped into the spotlight.

AEs in the 1970s and 80s worked multi-month, sometimes multi-year deals for minicomputers, networks, and software systems. They ran on-site demos, navigated procurement boards, built formal proposals, and coached executives through the adoption of technology most people had never touched.

This era gave the AE its identity as the “quarterback” of the deal. Reps weren’t pitching features; they were consultants. The title stuck because it captured something important: selling had become strategic. The “executive” title looked good on a business card and gave sellers the prestige (and confidence) they needed to sell to real executives.

The Inside Sales Revolution (1990s–2000s)

Then came CRM.

As companies adopted digital databases for leads and customer relationships, they discovered something: not every salesperson needed to be on the road. For the first time, reps could qualify prospects, log conversations, and route leads without leaving a desk. This sparked a wave of new titles like the Inside Sales Rep for high-velocity calling, the Lead Development Rep for early qualification, Business Development Rep for outbound, and the Account Manager for renewals and relationship management.

It was the first major structural split in modern sales: the hunters and the farmers, the outbound specialists and the closers. Companies realized you could make closing roles more efficient by removing prospecting from their plates.

2011: The SDR/BDR Model Goes Mainstream

The tipping point came when Salesforce formally separated prospecting from closing and published the playbook.

Aaron Ross’ Predictable Revenue described how Salesforce used inbound SDRs to qualify hand-raisers and outbound SDRs to hunt greenfield accounts, while AEs handled demos and closing. The model worked so well that companies copied it wholesale. Within a few years, “SDR” and “BDR” went from niche acronyms to almost mandatory roles in any tech company with a quota. Entire career ladders formed around them.

The modern sales assembly line — SDR → AE → CSM — was born.

When software moved to subscriptions, something subtle but important happened: the moment a deal closed was no longer the end of the journey. It was the beginning of a revenue relationship companies needed to protect.

Enter Customer Success Managers.

CSMs emerged to reduce churn, drive adoption, and expand accounts over time. For the first time, a sales-adjacent title existed with a mandate that wasn’t quota-first. Instead, it was customer-first, renewal-first, relationship-first.

Companies like Gainsight championed the discipline publicly. Industry groups formalized best practices. CSM became a standard pillar of any recurring revenue motion.

The CRO and RevOps Era (Late 2010s–Present)

As SaaS selling became more complex, executives realized the entire revenue engine needed orchestration.

That’s when the Chief Revenue Officer emerged, consolidating sales, marketing, and customer success leadership under a single owner of revenue.

Shortly after, Revenue Operations rose in prominence. RevOps became the glue that connected CRM systems, forecasting, enablement, compensation design, and GTM data.

Suddenly, job titles like: Director of RevOps, VP of GTM Strategy, Sales Enablement Manager were showing up everywhere.

The Org Chart Is a Story

Every GTM title we use today carries the fingerprint of a different decade:

- Territory reps from the IBM era.

- AEs from the rise of complex enterprise technology.

- SDRs/BDRs from Salesforce’s 2011 playbook.

- CSMs from SaaS economics.

- CROs and RevOps from the need to unify the entire funnel.