In the late 90s, a typical enterprise sales meeting began with a projector warming up, a room full of executives shifting in their chairs, and a consultant opening a laptop that sounded like it might lift off the table. The laptop ran Siebel. The interface looked intimidating, the demo always froze once or twice, and no one in the room agreed on whether it would actually make selling easier. But they all agreed they needed it.

But to understand how the CRM became central to selling, you have to understand how people sold before it.

Notebooks and Hope

Before Siebel, sales organizations functioned like small, isolated departments. Reps tracked deals in notebooks or personal spreadsheets. Managers built forecasts by asking reps to rate their gut feelings. Customer data lived in filing cabinets, personal Rolodexes, and the heads of whoever happened to be employed that quarter.

When a rep quit, they often took the entire customer relationship with them. If a prospect moved from early interest to late-stage evaluation, the only record of that journey lived in an AE’s handwritten notes.

Companies had no unified view of anything. If you asked a VP of Sales for a pipeline update, the answer ranged from optimistic storytelling to pure invention. In that environment, the idea of a system that captured everything in one place sounded like an impossible luxury. Tom Siebel thought it could be real.

Tom Siebel Sees the Future

Siebel began his career at Oracle, and by the late 80s he had built a reputation as a talented, aggressive operator who understood how software could transform large enterprises. He also clashed with Larry Ellison often enough that his departure felt inevitable. When he left Oracle in 1993, he took with him an idea that Oracle had not prioritized: software built specifically for sales teams.

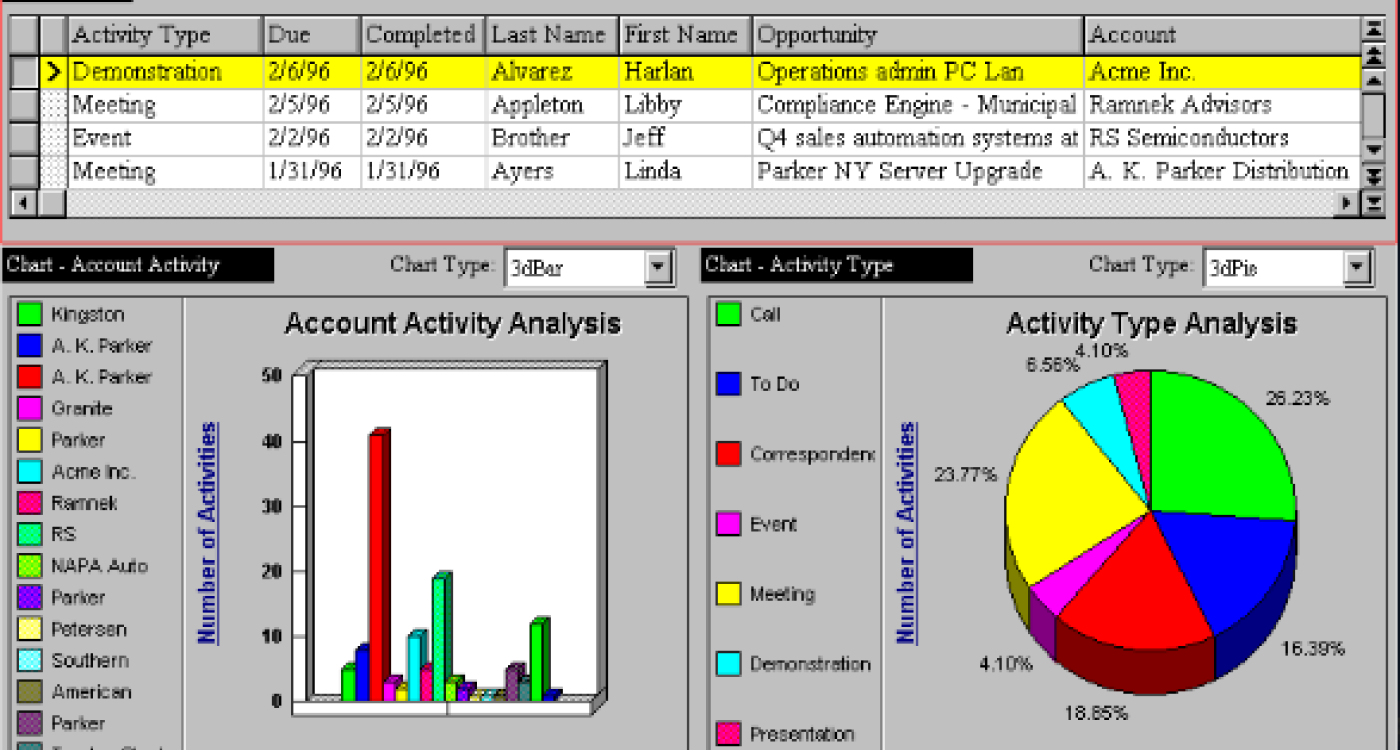

He founded Siebel Systems with the belief that companies needed a dedicated platform that organized customer information at a level no spreadsheet or homegrown database ever could. In theory, the idea was simple: record every contact, track every deal, document every interaction, and surface everything for leadership. In practice, it required complex software, long implementation cycles, and a level of organizational change that many companies resisted.

But once one major company adopted it, everyone else followed. No executive wanted to be the last person running a national sales team from a pile of paper reports.

The Climb to Dominance

Siebel Systems grew faster than almost any software company of its era. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, Siebel became the default choice for enterprises in finance, telecom, pharmaceuticals, manufacturing, and tech.

The product itself was powerful but famously difficult. Installing Siebel often required an army of consultants. Customizing it meant long meetings, long invoices, and long nights for IT teams. Reps complained that updating fields interrupted their flow. Managers loved the visibility. Executives loved the promise of control.

Despite the pain, Siebel gave companies something they had never seen before: a shared operating reality. Leaders could view national pipeline trends without chasing down individual reps. Renewal cycles had structure. Marketing and sales could argue over the same data instead of arguing over separate spreadsheets. For large companies in the 90s, this felt transformational.

The Fall and the Successor

The same qualities that made Siebel powerful also made it vulnerable. As the cloud era took shape in the early 2000s, companies began questioning why they needed massive on-premise installations that cost millions and required constant maintenance. They started looking for something lighter, faster, and easier to adopt.

Salesforce arrived with a clear message: software should run in the browser, not in a server room. The shift from installed software to cloud applications changed the entire economics of CRM. Siebel Systems could not move quickly enough, and in 2006, it was acquired by Oracle.

In a twist of fate, Siebel Systems ended up right back where Tom Siebel began his career.

The Legacy That Never Went Away

Even though Siebel disappeared as a standalone company, its influence is everywhere. The structure of modern CRMs comes from Siebel’s early ideas: contacts, accounts, opportunities, pipeline stages, forecasting tools, dashboards, and reporting hierarchies. Every rep who updates fields in Salesforce or HubSpot is working inside a framework Siebel pioneered. Every CRO who relies on forecasting reports is using concepts Siebel introduced to the mainstream. Every conflict between reps and managers over documentation has roots in the same early battles.

The CRM that sales teams use today looks cleaner and runs faster, but the logic behind it belongs to the 90s. Siebel wrote the first draft. Salesforce simply built the cloud version. Siebel Systems may be gone, but its blueprint is the backbone of modern selling.